Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Trauma Inj > Volume 30(4); 2017 > Article

-

Case Report

Isolated Dissection of the Celiac Artery after Blunt Trauma: A Case Report and Review of Literature - Ahram Han, M.D.1, Jihun Gwak, M.D.1, Gangkook Choi, M.D.1, Jae Jeong Park, M.D.1, Byungchul Yu, M.D.1, Gil Jae Lee, M.D.1, Jin Mo Kang, M.D.2

-

Journal of Trauma and Injury 2017;30(4):220-226.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20408/jti.2017.30.4.220

Published online: December 30, 2017

- 5,832 Views

- 104 Download

- 7 Crossref

1Department of Trauma Surgery, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, Incheon, Korea

2Department of Surgery, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, Incheon, Korea

- Correspondence to: Jin Mo Kang, M.D., Department of Surgery, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, 21 Namdong-daero 774beon-gil, Namdong-gu, Incheon 21565, Korea, Tel: +82-32-460-3247, Fax: +82-32-460-3244, E-mail: calzevi@gmail.com

Copyright © 2017 The Korean Society of Trauma

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

- Traumatic dissection of the celiac artery without aortic dissection is a rare event. Here we describe two cases of celiac artery dissection after blunt abdominal trauma managed conservatively without surgical or endovascular intervention.

- Fewer than 10 cases of isolated celiac artery (CA) dissection following blunt trauma have been reported. Because of its rarity, there is yet no consensus on management of isolated CA dissection in terms of the timing and necessity of medical or interventional therapy. Reported here are 2 cases of traumatic CA dissection with a review of the literature regarding the clinical presentation and management of this injury.

INTRODUCTION

- Case 1

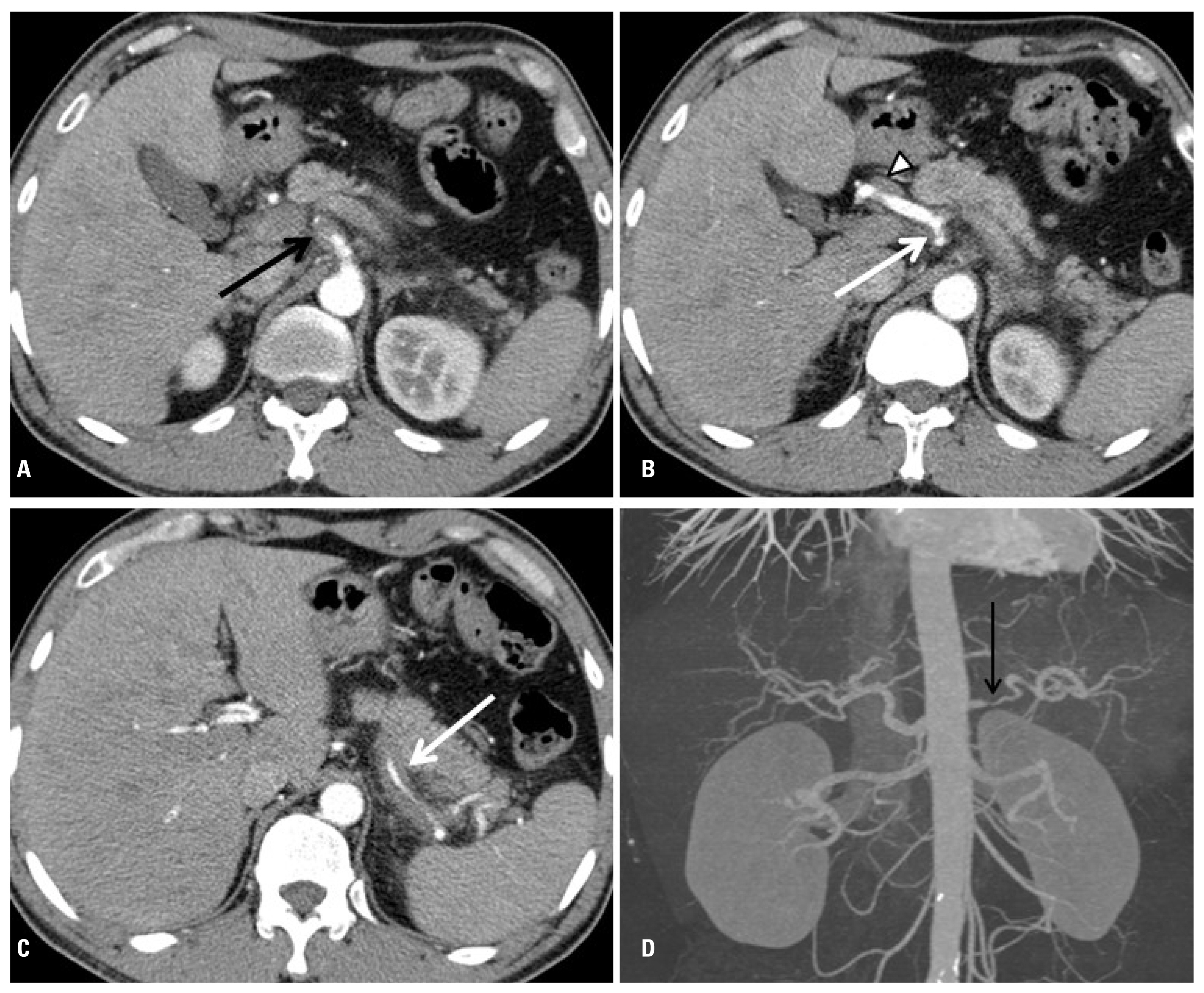

- A 68-year-old man with no previous medical history was transferred to our hospital after he was struck by a motorcycle while riding his bicycle. The initial blow was to his right anterior chest, and he was knocked off the bicycle onto his back. He was alert and hemodynamically stable at admission, and was complaining of epigastric pain and right chest wall and low back pain. However, he did not have abdominal tenderness or peritoneal signs on physical examination. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen showed multiple rib fractures on the right side, fractures of the transverse processes of second and third lumbar vertebrae, and CA dissection with a focal intimal flap extending from approximately 1 cm below the origin to the trifurcation (Fig. 1). The hepatic, left gastric, and splenic arteries were well visualized and the liver and spleen showed homogenous enhancement. The superior and inferior mesenteric arteries were patent with normal caliber. Laboratory findings showed slight elevations of the liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase, 44 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 41 U/L; total bilirubin, 1.4 mg/dL) and the lactate dehydrogenase level was 1,038 U/L.

- We decided to manage the patient conservatively with antiplatelet therapy. Repeat CT angiography at hospital day 3 showed persistent CA dissection without progression, and a liquid diet was started. The patient was discharged on hospital day 6 after being on a regular diet for 2 days. His liver enzymes were normalized at the time of discharge. The patient, who was lost to follow up after discharge, was contacted by telephone 18 months later and he reported that he had been free of abdominal symptoms and had no change in eating habits or body weight since the injury.

- Case 2

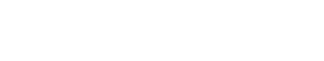

- A 49-year-old man who was a non-smoker with no previous medical history presented to our emergency department after being diagnosed with possible pancreatitis at his local hospital. He had been involved in a motorcycle accident 10 days earlier during which he lost control of the vehicle and was ejected. He had no abdominal symptoms immediately after the accident, and was initially evaluated only for superficial facial injuries and a painful right thigh. However, 8 days later, he developed a progressively worsening epigastric pain. The pain had no relationship to meals or posture. By the time he returned to the hospital, the pain was severe (pain score 7/10) and was radiating to the left back. His white blood count and C-reactive protein level were mildly elevated (10.42×103/mm3 and 6.41 mg/dL, respectively), but the amylase and lipase levels were normal, contrary to the presumptive diagnosis of pancreatitis. The abdominal CT scan showed an intimal flap within the CA with an associated focal thrombus involving the false lumen (Fig. 2). The injury extended into the proximal common hepatic artery and the splenic artery, and there was infiltration of the soft tissue around the three involved arteries. The splenic artery was markedly narrowed with an attenuated signal along its suprapancreatic course. We initiated anticoagulation with conventional heparin therapy and the abdominal pain was resolved within one day. Repeat CT angiography on hospital day 3 showed a slight decrease in the soft tissue density around the CA and the common hepatic and splenic arteries, and there was improved flow in the splenic artery, although there was no change in the extent of thrombus or dissection in the CA. The patient was discharged the next day with oral antiplatelet treatment, and remained symptom-free during the first month of follow-up. We plan to repeat CT angiography at 6 months, and yearly thereafter.

CASE REPORT

- Abdominal vascular injuries caused by blunt trauma are uncommon, with a reported incidence of 5 to 10% [1]. Isolated CA injury, which is an injury to the CA without concomitant aortic injury, is the least common among all abdominal arterial injuries. To date, only 8 reports of isolated CA injury following blunt trauma have been reported [2–9]. These cases, except for 1 case without a detailed description, are summarized, along with our two cases, in Table 1. All but one of the injuries (CA rupture managed by surgical ligation) [3], including our two cases, were CA dissections. In this report, we focus on the clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes of these isolated CA dissections.

- All of the reported traumatic CA dissections were in male patients. Whether this is associated with the known male preponderance of spontaneous CA dissection [10] needs to be validated. The traumatic CA dissections were associated with various blunt injuries, and not all were associated with a direct blow to the abdomen, indicating there may be other mechanisms underlying the development of CA dissection. Some authors have suggested that celiac trunk compression by an anomalous median arcuate ligament during rapid expiration may compress and injure the CA [11], while the possible role of other predisposing factors, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, smoking history, and collagen vascular disease has also been investigated in spontaneous CA dissection, although the results so far have been inconclusive.

- The clinical presentation of CA dissection varies widely, from no symptoms to severe epigastric pain. Among symptomatic patients, abdominal pain is the most common symptom, and often begins several days after the initial injury. More than half of the reported patients had elevated liver enzymes, but this is of low diagnostic value because mild elevations of the hepatic enzymes are also commonly associated with liver contusion or muscle injuries after blunt abdominal trauma. However, an acute elevation of liver enzymes in a patient with known traumatic CA dissection should warrant further evaluation, because it may be a sign of liver necrosis from hepatic artery involvement [4]. Among all reported cases of traumatic CA dissection, 4 showed involvement of branches of the CA (splenic artery and common hepatic artery, n=3 and common hepatic artery only, n=1).

- All of the reported traumatic CA dissections have been diagnosed by contrast-enhanced CT. CT has become the primary modality of radiologic evaluation for blunt trauma patients, and has been shown to be useful in detecting arterial injuries [12,13]. However, focal dissections of the CA can be missed by standard single-phase images with 5-mm thick sections [5], and we recommend repeat CT angiography or three-phase abdominal CT with 3-mm sections with reconstructed multiplanar images when injuries to visceral arteries are suspected and the initial CT is nondiagnostic. Common CT findings of CA dissections are intimal flap, thrombosed false lumen, segmental fat infiltration, aneurysmal dilatation of CA, and extension of dissection into branch arteries [14].

- Because of its rarity, as well as the diverse clinical course and outcomes of the reported cases of traumatic isolated CA dissection, there are no agreed-upon recommendations for when and how to treat this injury. Some patients with traumatic CA dissections, including ours, have been managed with antiplatelet therapy (n=3; aspirin 81 mg or 100 mg), anticoagulation (n=3; enoxaparin or heparin converted to warfarin for 3 months), or endovascular stenting (n=1) in addition to blood pressure control. Recent experience with nontraumatic isolated CA dissection also supports conservative management with antiplatelet medication, anticoagulants, or no medication in patients without ischemic or hemorrhagic complications [10,15–17]. Antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants are commonly used to stabilize the injured arterial wall and prevent thrombotic occlusion of the involved arteries. However, some authors advocate that these antithrombotic drugs should not be used in acute visceral artery dissections, as it will delay thrombosis of the false lumen and possibly thereby lead to propagation of the dissection [18]. Although there has been no direct comparison, a recent systemic review showed that outcomes of spontaneous CA dissection were good regardless of the conservative treatment chosen [10].

- As in nontraumatic CA dissection, surgical or endovascular intervention should be considered in patients with persistent symptoms, aneurysmal change, or hemorrhagic complications. Endovascular stenting or embolization is preferred over surgery because it is relatively less invasive. Surgical therapy is usually reserved only for patients who need revascularization of multiple branch arteries.

- Obstruction of the celiac artery or its branches, either as a complication of CA dissection or following therapeutic ligation or embolization, rarely leads to organ ischemia because of the abundant collateral circulation. Even in the rare cases where thrombosis accompanying CA dissection has caused partial splenic infarct, pancreatitis, or liver dysfunction, the patients have been managed successfully with conservative measures [16,17]. However, close observation is important because two lethal ischemic complications, fulminant hepatic failure after traumatic CA dissection [4], and multiple organ ischemia leading to septic shock after spontaneous CA dissection [19], have been reported. Late aneurysmal change is another feared complication, and is detected in 6% of patients with conservatively managed spontaneous CA dissections [10]. Repair is generally necessary when the aneurysm is over 2 to 3 cm in size.

- Most of the aneurysmal changes after traumatic CA dissection have occurred within 2 months [10], but they have also been detected as late as the fourth year [20], which highlights the importance of long term follow-up for patients with CA dissection.

- In summary, isolated celiac artery dissection is a rare occurrence after blunt trauma. Uncomplicated cases can be safely managed conservatively with or without antithrombotic therapy plus blood pressure control. Long term follow-up is mandatory because of the risk of late aneurysmal change.

DISCUSSION

| Age/sex | Predisposing factora | Mechanism | Clinical findingb | CT finding | Associated injury | Treatment | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linuma et al. (2006)[3] | 39/M | N/S | Crush injury | Severe epigastric pain, severe abdominal tenderness, elevation of WBC, LFT, LDH | Extravasation from a minor tear of CA | None | Surgical ligation | D/C at POD #16 |

| Kirchhoff et al. (2007)[4] | 66/M | N/S | MVA | Liver failure (PID #6) |

CA flap with wall hematoma CA-CHA thrombosis, liver necrosis |

TBI, MRF, bilateral HPTx | None | Death d/t fulminant hepatic failure (HOD #7) |

| Suchak et al. (2007) [5] | 41/M | Hypertension | MVA - rollover | Severe epigastric pain (PID #2) | Intimal flap in proximal CA | Muscle contusion | Endovascular self-expandable stent | Symptom resolved after stent |

| Gorra et al. (2009) [6] | 29/M | N/S | Fall (9 m) | Midback pain, mild LFT elevation | CA dissection with periarterial stranding | Humerus Fx., pelvic Fx., pulmonary contusion | Anticoagulation (heparin → warfarin) 3 Mo | f/u CT (3 Mo) : complete occlusion of CA with collateral flow to branches |

| Laeseke and Gayer (2012) [7] | 47/M | N/S | Motorcycle TA (abdomen hit by handle bar) | Mild epigastric, LUQ pain, feeling of distension, nausea elevation of LFT, lipase | Intimal injury and focal thrombus involving distal CA, proximal CHA, SA | None | Aspirin 81 mg | Lost to f/u |

| Sarkar et al. (2012) [8] | 26/M | N/S | MVA - ejected from vehicle | No symptoms | Focal dissection near origin of CA | Open tibia fibula Fx., MRF, L1-L3 TP Fx. | Anticoagulation (enoxaparin → warfarin) 3 Mo | f/u CT (3 Mo): complete resolution of dissection |

| Rosenthal et al. (2015) [9] | 26/M | N/S | Fall (46 m) into a river | No symptoms, LFT elevation |

85% stenosis of CA, Dissection 7 mm from CA origin Adjacent soft tissue stranding |

PTx, hemurus Fx., T4, T5 Fx., talus Fx., MRF | Aspirin 81 mg | f/u CT (1 week) : persistent CA dissection, moderate stenosis |

| Present case 1 | 68/M | Old age | Bicycle TA -with a motorcycle | Epigastric pain mild elevation of LFT, LDH | Focal intimal flap : 1 cm distal to CA origin to trifurcation | MRF, L2-3 TP Fx. | Aspirin 100 mg, 3 Mo | D/C at HOD #6, symptom free for 18 Mo |

| Present case 2 | 49/M | Mild atherosclerosis on CT | Motorcycle TA | Epigastric pain radiating to left back (PID #8) |

CA dissection with focal thrombus Narrowing of CHA and SA with perivascular soft tissue stranding |

Thigh contusion | Anticoagulation (heparin, 3 days) → aspirin 100 mg 3 Mo | D/C at HOD #4 symptom-free for 1 Mo |

CT: computed tomography, M: male, S: none specified, WBC: white blood cell, LFT: liver function test, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, CA: celiac artery, D/C: discharge, POD: postoperative day, MVA: motor vehicle accident, PID: post-injury day, CHA: common hepatic artery, TBI: traumatic brain injury, MRF: multiple rib fracture, HPTx: hemopneumothorax, HOD: hospital day, Fx.: fracture, Mo: month, f/u: follow-up, TA: traffic accident, LUQ: left upper quadrant, TP: transverse process, SA: splenic artery.

a Presence of known predisposing factors of arterial dissection.

b All symptoms, signs, and laboratory result that are possibly related to celiac artery dissection in each case are listed.

- 1. Asensio JA, Soto SN, Forno W, Roldan G, Petrone P, Gambaro E, et al. Abdominal vascular injuries: the trauma surgeon’s challenge. Surg Today 2001;31:949–57.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 2. Asensio JA, Petrone P, Kimbrell B, Kuncir E. Lessons learned in the management of thirteen celiac axis injuries. South Med J 2005;98:462–6.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Linuma Y, Yamazaki Y, Hirose Y, Kinoshita H, Kumagai K, Tanaka T, et al. A case of isolated celiac axis injury by blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 2006;61:451–3.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Kirchhoff C, Stegmaier J, Krotz M, Muetzel Rauch E, Mutschler W, Kanz KG, et al. Celiac dissection after blunt abdominal trauma complicated by acute hepatic failure: case report and review of literature. J Vasc Surg 2007;46:576–80.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Suchak AA, Reich D, Ritchie W. Traumatic isolated dissection of the celiac artery. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;189:W373–4.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Gorra AS, Mittleider D, Clark DE, Gibbs M. Asymptomatic isolated celiac artery dissection after a fall. Arch Surg 2009;144:279–81.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Laeseke PF, Gayer G. An uncommon cause of abdominal pain following blunt abdominal trauma. Br J Radiol 2012;85:1025–6.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Sarkar J, Plackett TP, Kellicut DC, Edwards KD. A case report of coeliac artery dissection following a motor vehicle collision. Injury Extra 2012;43:15–7.Article

- 9. Rosenthal MG, Cunningham J, Habib J, Kerwin AJ. Isolated celiac artery dissection in blunt abdominal trauma. Am Surg 2015;81:E287–90.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Cavalcante RN, Motta-Leal-Filho JM, De Fina B, Galastri FL, Affonso BB, de Amorim JE, et al. Systematic literature review on evaluation and management of isolated spontaneous celiac trunk dissection. Ann Vasc Surg 2016;34:274–9.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Watanabe A, Kohtake H, Furui S, Takeshita K, Ishikawa Y, Morita S. Celiac artery dissection seen with ruptured pancreaticoduodenal arcade aneurysms in two cases of celiac artery stenosis from compression by median arcuate ligament. J Vasc Surg 2012;56:1114–8.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Yao DC, Jeffrey RB Jr, Mirvis SE, Weekes A, Federle MP, Kim C, et al. Using contrast-enhanced helical CT to visualize arterial extravasation after blunt abdominal trauma: incidence and organ distribution. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;178:17–20.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Peng PD, Spain DA, Tataria M, Hellinger JC, Rubin GD, Brundage SI. CT angiography effectively evaluates extremity vascular trauma. Am Surg 2008;74:103–7.ArticlePubMed

- 14. D’Ambrosio N, Friedman B, Siegel D, Katz D, Newatia A, Hines J. Spontaneous isolated dissection of the celiac artery: CT findings in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188:W506–11.ArticlePubMed

- 15. DiMusto PD, Oberdoerster MM, Criado E. Isolated celiac artery dissection. J Vasc Surg 2015;61:972–6.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Ichiba T, Hara M, Yunoki K, Urashima M, Naitou H. Impact of noninvasive conservative medical treatment for symptomatic isolated celiac artery dissection. Circ J 2016;80:1445–51.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Hosaka A, Nemoto M, Miyata T. Outcomes of conservative management of spontaneous celiac artery dissection. J Vasc Surg 2017;65:760–5.e1.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Min SI, Yoon KC, Min SK, Ahn SH, Jae HJ, Chung JW, et al. Current strategy for the treatment of symptomatic spontaneous isolated dissection of superior mesenteric artery. J Vasc Surg 2011;54:461–6.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Schaeffer E, Landy C, Masson Y, Nadaud J, Plancade D. Spontaneous celiac trunk dissection complicated by multiple visceral ischaemia: a case report. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2013;32:e77–8.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Galastri FL, Cavalcante RN, Motta-Leal-Filho JM, De Fina B, Affonso BB, de Amorim JE, et al. Evaluation and management of symptomatic isolated spontaneous celiac trunk dissection. Vasc Med 2015;20:358–63.ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Isolated celiac artery injury: Brief report, review of literature, and suggested grading guidelines

Kanani Fahim, Neeman Uri, Hashavia Eyal, Timor Idit, Soffer Dror, Shimonovich Shachar

Trauma.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Endovascular Stenting in a Rare Case of Multiple Spontaneous Visceral Arterial Dissections

Jacxelyn Moran, Naveen Galla, Mona Ranade

Vascular and Endovascular Surgery.2021; 55(3): 269. CrossRef - Evaluation of isolated abdominal visceral artery dissection with multi-scale spiral computed tomography: a retrospective case series

Qizhou He, Fei Yu, Yajun Fu, Bin Yang, Ran Huo, Rong Xian, Shulan Liu, Kali Liang, Guangcai Tang

Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Diagnosis and treatment of isolated celiac artery dissection following blunt trauma: A case report

Tohru Ishimine, Takahiro Ishigami, Kohei Chida, Kyohei Kawasaki, Naoki Taniguchi, Toshiho Tengan

International Journal of Surgery Case Reports.2021; 89: 106617. CrossRef - Retrospective Analysis and Systematic Review of Isolated Traumatic Dissections of the Celiac Artery

Jens Birkl, Thomas Kahl, Henryk Thielemann, Sven Mutze, Leonie Goelz

Annals of Vascular Surgery.2020; 66: 250. CrossRef - Traumatic dissection of the coeliac artery and splenic injury following blunt trauma

Bobby Vincent Li, Ramesh Damodaran Prabha, Maruthi Narra, Hung Nguyen

BMJ Case Reports.2019; 12(8): e229405. CrossRef - Symptomatic Isolated Celiac Artery Dissection following Blunt Trauma

Sang Bong Lee, Hyuk Jae Jung, Jae Hun Kim

Journal of Acute Care Surgery.2019; 9(2): 76. CrossRef

KST

KST

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite