Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Trauma Inj > Volume 32(1); 2019 > Article

-

Original Article

Development of Korean Teaching Model for Surgical Procedures in Trauma -Essential Surgical Procedures in Trauma Course- - Hohyun Kim, M.D.1,2,3, Chan-Yong Park, M.D.3,4, Hyun-Min Cho, M.D.1,2,3, Kwang-Hee Yeo, M.D.1,2,3, Jae Hun Kim, M.D.1,2,3, Byungchul Yu, M.D.3,5, Seung-Je Go, M.D.3,6, Oh Sang Kwon, M.D.3,7

-

Journal of Trauma and Injury 2019;32(1):8-16.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20408/jti.2018.051

Published online: March 31, 2019

- 3,947 Views

- 68 Download

1Department of Trauma Surgery, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea

2Biomedical Research Institute, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea

3Korean Association for Research, Procedure and Education on Trauma (KARPET), Seoul, Korea

4Department of Trauma Surgery, Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan, Korea

5Trauma Center, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, Incheon, Korea

6Department of Trauma Surgery, Trauma Center, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea

7Traumatology, Regional Trauma Center, Cheju Halla General Hospital, Jeju, Korea

- Correspondence to: Chan-Yong Park, M.D., Department of Trauma Surgery, Wonkwang University Hospital, 895 Muwang-ro, Iksan 54538, Korea, Tel: +82-63-859-0122, Fax: +82-63-859-0125, E-mail: kim-noah@hanmail.net

Copyright © 2019 The Korean Society of Trauma

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

Purpose

- The Essential Surgical Procedures in Trauma (ESPIT) course was developed as a model to teach necessary surgical procedures to trauma physicians. Its goals are to improve knowledge, self-confidence, and technical competence.

-

Methods

- The ESPIT course consisted of five lectures and a porcine lab operative experience. The ESPIT course has been run seven times between February 2014 and April 2016. ESPIT participants completed a questionnaire to assess self-efficacy regarding essential surgical procedures in trauma before and immediately after taking the ESPIT course. Sixty-three participants who completed both pre- and post-course questionnaires on self-efficacy were enrolled in this study.

-

Results

- The overall post-ESPIT mean self-efficacy score was higher than the pre-ESPIT mean self-efficacy score (8.3±1.30 and 4.5±2.13, respectively) (p<0.001). Self-efficacy was significantly improved after the ESPIT course in general surgeons (p<0.001), thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons (p<0.001), emergency medicine doctors, and others (neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons) (p<0.001). The differences in self-efficacy score according to career stage (<1 year, 1–3 years, 3–5 years, and >5 years) were also statistically significant (p<0.001).

-

Conclusions

- The data of the ESPIT participants indicated that they felt that the ESPIT course improved their self-efficacy with regard to essential surgical procedures in trauma. The ESPIT course may be an effective strategy for teaching surgical procedures, thus promoting better management of traumatic injuries.

- With the widespread use of non-operative management in recent years, the number of trauma surgical operations has decreased [1]. Therefore, different institutes perform from dozens to hundreds of surgeries for cases of severe trauma per year. Thus, it may be difficult to maintain and improve skills in this area with on-the-job training alone. This tendency is similar in Western countries, and off-the-job training programs, such as the Advanced Trauma Operative Management (ATOM) course [1–5], advanced surgical skills for exposure in trauma (ASSET) [6–8], and the Definitive Surgical Trauma Care (DSTC) course [9,10], have been implemented to supplement on-the-job training. Many young surgeons wish to learn new skills, train in various surgical procedures, and improve both their expertise. It is important to build attractive training facilities that can respond to these demands and create a training system to foster young emergency physicians and emergency surgeons.

- The Essential Surgical Procedures in Trauma (ESPIT) course was developed in 2014 to educate trauma physicians regarding essential surgical procedures for use in cases of trauma. This study was performed to investigate the effect on self-efficacy from the ESPIT course and to develop a Korean teaching model for surgical procedures in trauma.

INTRODUCTION

- ESPIT course development

- The ESPIT course is administered by the Korean Association for Research, Procedures, and Education in Trauma (KARPET), which is organized by the Korean Society of Traumatology (KST). The contents of the ESPIT course were developed by a panel of experienced traumatologists. Eleven experts met in January 2014 to determine whether the course content reflected relevant and current information about the most common injuries, and whether the surgical procedures adhered to standard practices. Specific organs and injuries were targeted that reflect the most common injuries of the torso. They discussed the course contents and procedures, and made suggestions regarding inclusion and omission of important topics. Several revisions to ESPIT have been made based on the judgments of these experts.

- Subjects of education

- Target of the ESPIT course are 1) fellows working in trauma specialist training institutions; 2) military doctor and officer working for military hospitals or headquarters; 3) experts with an interest in trauma techniques for seriously injured patients; and 4) emergency medical and surgical residents with an interest in trauma.

- Education goals

- The objectives of the ESPIT course are to ensure that participants are able to apply surgical airway procedures in emergency situations, carry out basic procedures required in treatment of chest injury, to enforce the basic surgical techniques associated with abdominal injury, understand the basic extended-focused assessment with sonography for trauma (E-FAST), and have the ability to apply the clinical techniques of E-FAST in actual emergency situations.

- ESPIT course curriculum

- The ESPIT course consists of five lectures (on the airway, chest, abdominopelvic, case discussion, E-FAST), a hands-on course. The hands-on training courses are composed of nine procedures, i.e., E-FAST, percutaneous cricothyroidotomy, open cricothyroidotomy, percutaneous tracheostomy, open tracheostomy, closed thoracostomy, resuscitative thoracotomy, emergency laparotomy, and damage control laparotomy (Table 1).

- The ESPIT curriculum allows participation as a provider, vice-instructor, instructor, or faculty member. Participants use animal models to acquire experience in surgical airway, chest injury, and abdominal injury methodologies. Providers obtain a provider certificate after completion of the ESPIT course. Vice-instructors closely observe the instructor process by participating in the vice-instructor course within 1 year after acquiring their provider certificate. Participants can earn an instructor certificate 1 year after obtaining the vice-instructor certificate by participating in the instructor course. Instructors participate in lectures and implement practical education based on scenarios of patients with major trauma. After obtaining the instructor certificate, an individual can participate continuously in the curriculum as a faculty member after obtaining approval from KARPET.

- Instruments of course evaluation

- To evaluate ESPIT, a comprehensive assessment was designed to measure participant learning in the affective and psychomotor domains. For the affective domain, a nine-question questionnaire was designed to reflect the skills taught in the course. Self-efficacy refers to judgments of one’s own ability to achieve success [11]. The self-efficacy questionnaire requires that participants rate their confidence in performing nine tasks involved in surgical procedures for trauma on a scale of 0–10, where scores of 0 and 10 indicated very little confidence and a great deal of confidence, respectively, with a highest possible total score of 90 (Table 2). Each participant’s total score was then divided by 9 (the number of items) to approximate their overall confidence level.

- An operative performance evaluation was designed for the psychomotor domain. The participants were judged on a checklist reflecting the degree of competence, with “Yes” awarded if they completed the task independently or “No” if they could not successfully complete the task. To ensure consistent use of the operative performance evaluation, instructors were briefed regarding the critical behaviors that each participant was required to perform.

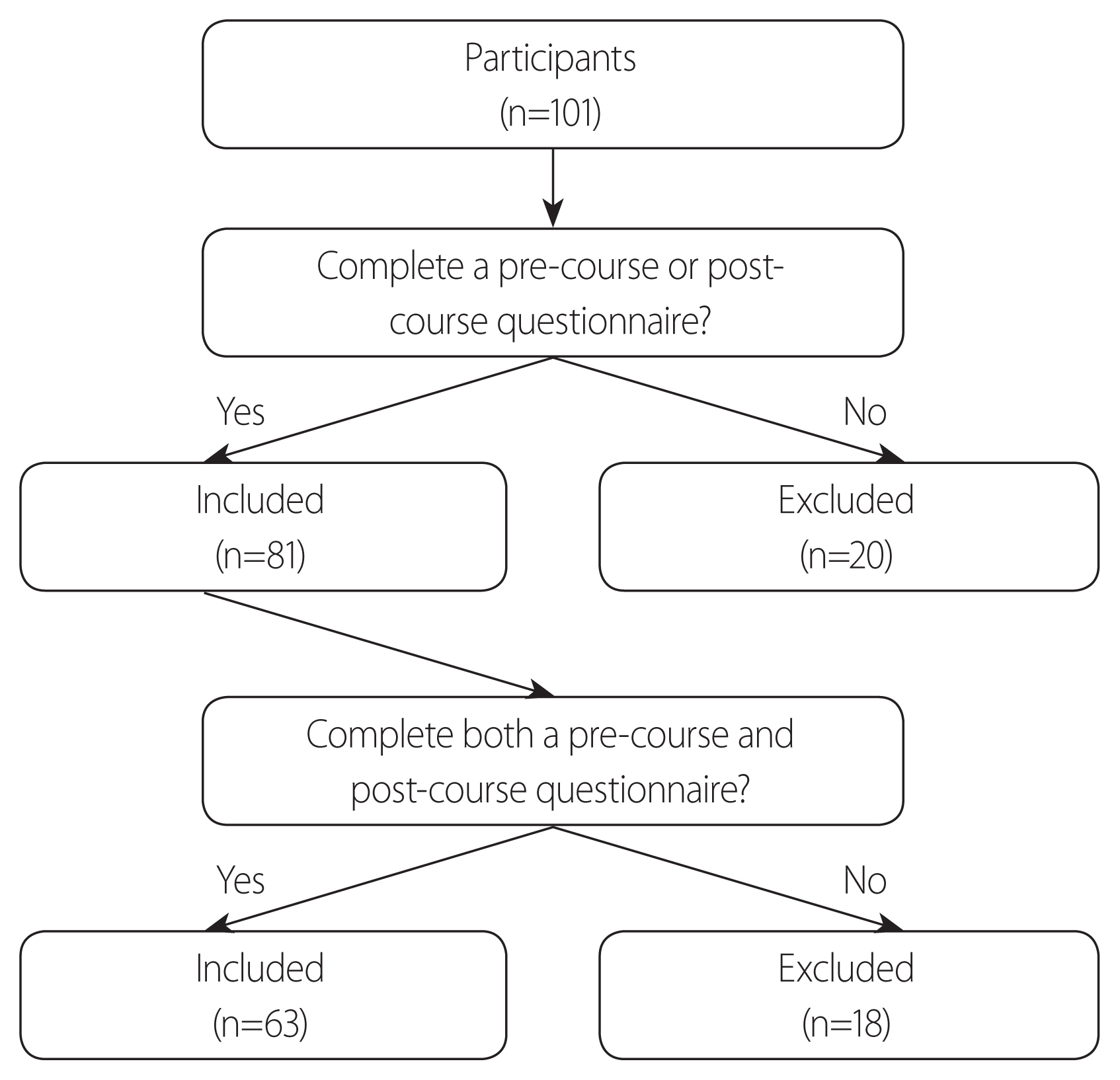

- Participants

- The ESPIT course was run seven times between February 2014 and April 2016, with the participation of a total of 101 doctors. ESPIT participants completed a questionnaire before and immediately after taking the ESPIT course. Eighty-one participants, consisting of 36 general surgeons, 12 thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons, 13 emergency medicine doctors, and 20 other doctors (such as neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and plastic surgeons), completed a pre-course and/or post-course questionnaire (Supplementary Files 1, 2, respectively) (Table 3). Eighteen of the eighty-one participants were excluded from the analysis because they did not complete either the pre-course or the post-course questionnaire”. Therefore, a total of 63 participants were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1).

- Animals

- The ESPIT course is held in the Medtronic Innovation Center (MIC), Osong, Sejong, Korea. The animals used in this study were owned by the MIC, and this project received research approval from the Research Ethics Board of the MIC. Four 3–6 months swine weighing 24.55±2.25 kg were used in the ESPIT course. After education, the animals were sacrificed by rapid intravenous injection of 20 mL of 10% potassium chloride.

- Statistical analysis

- The mean scores±standard deviation were examined to evaluate the experts’ ratings regarding the course content and procedures, as evidence to support use of the self-efficacy instruments across the known groups, and to describe ratings of the course and instructor evaluations. Self-efficacy scores were tested for significant improvements from pre- to post-course using Student’s t-test for paired samples. Wilcoxon’s signed rank test was used to compare differences in operative performance between groups. SPSS ver. 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA ver. 12.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) were used to analyze the data. In all analyses, p<0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

METHODS

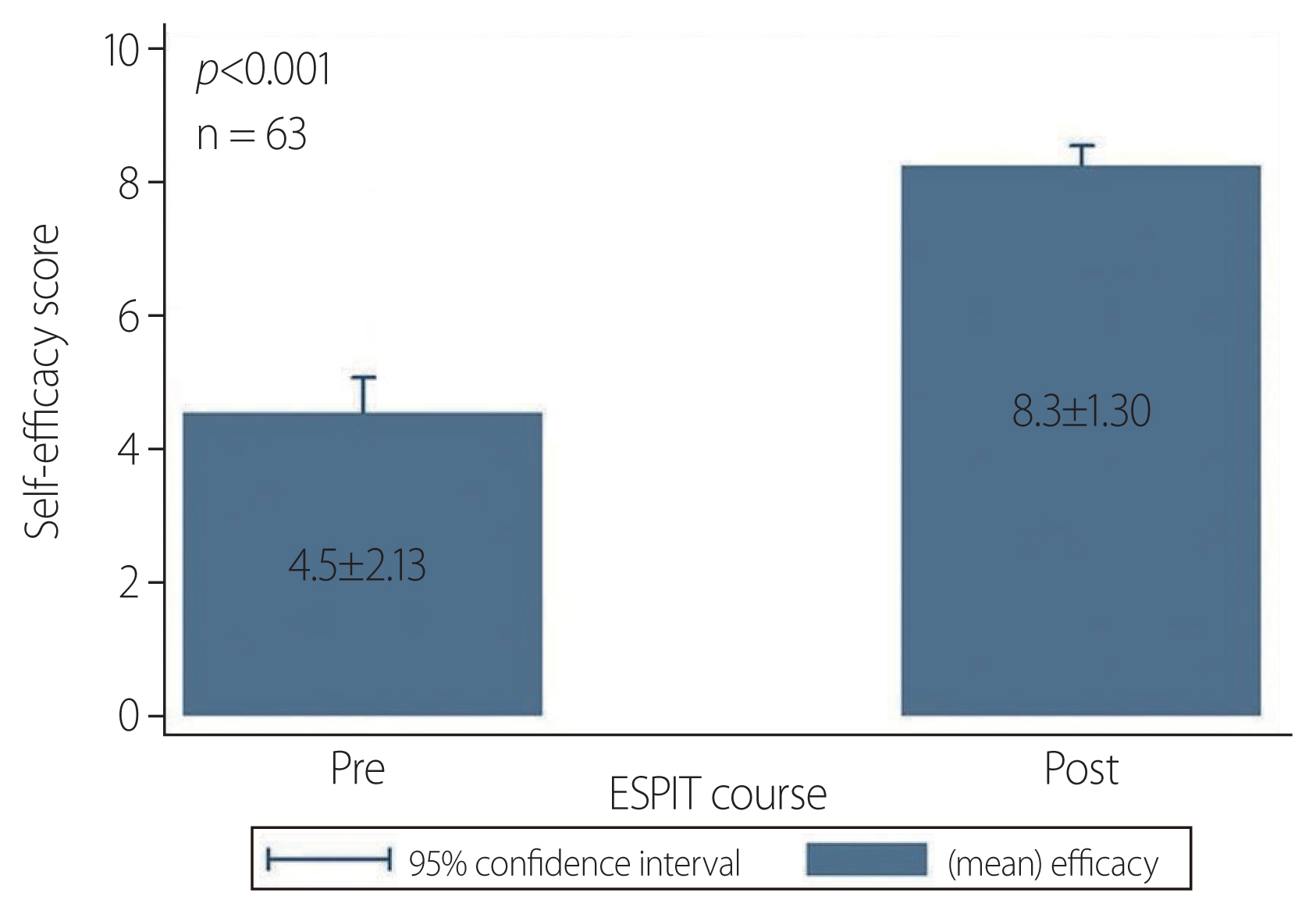

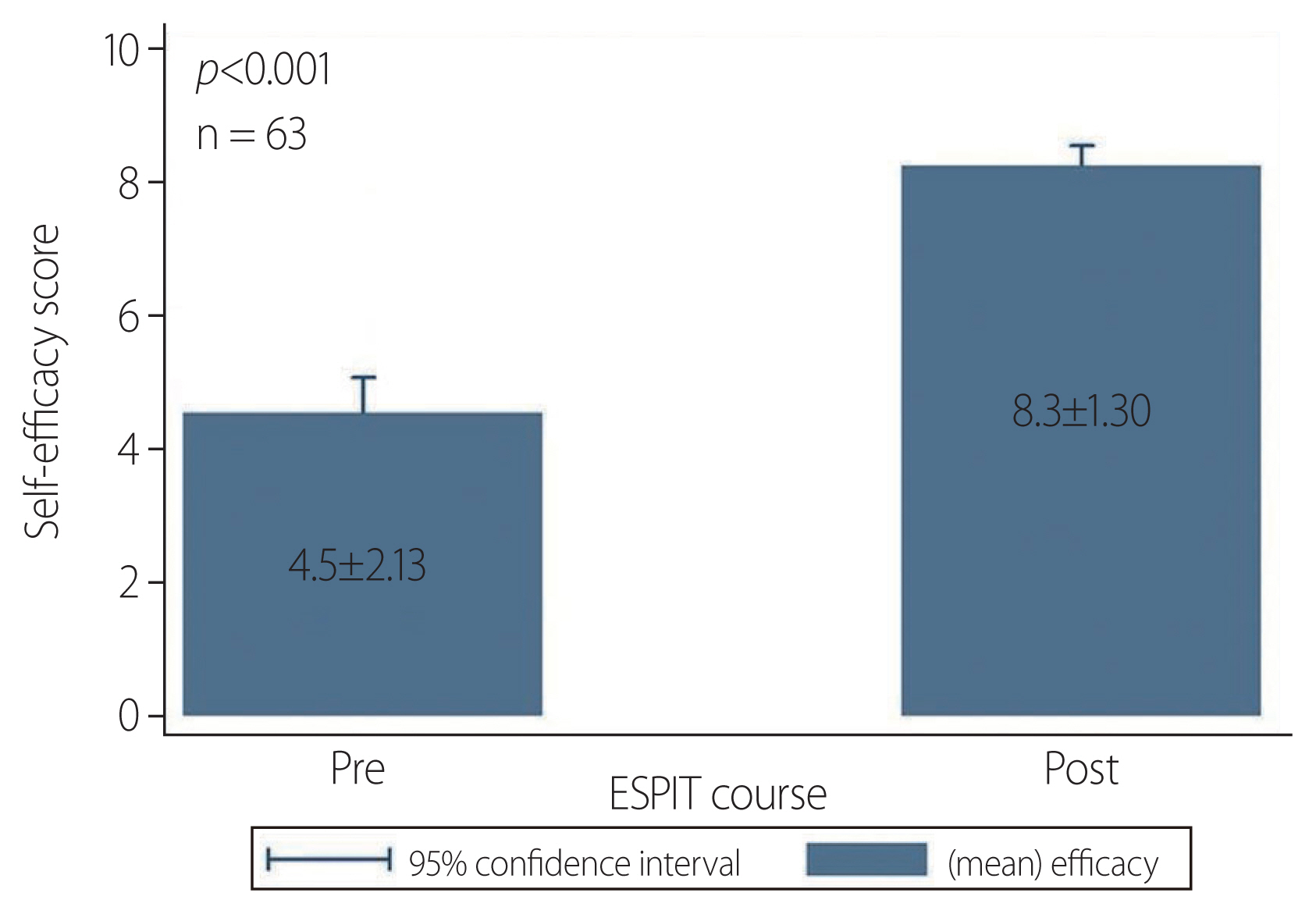

- In total, 63 participants, consisting of 28 general surgeons, six thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons, 11 emergency medicine doctors, 11 orthopedic surgeons, and seven neurosurgeons, completed both pre- and post-course questionnaires on self-efficacy. The overall self-efficacy score increased after taking the ESPIT course for all procedures (pre-course, 4.5±2.13; post-course, 8.3±1.30; p<0.001) (Fig. 2). Improvement of self-efficacy score was highest in resuscitative thoracotomy (pre-course, 3.19±2.92; post-course, 7.87±1.69; p<0.001).

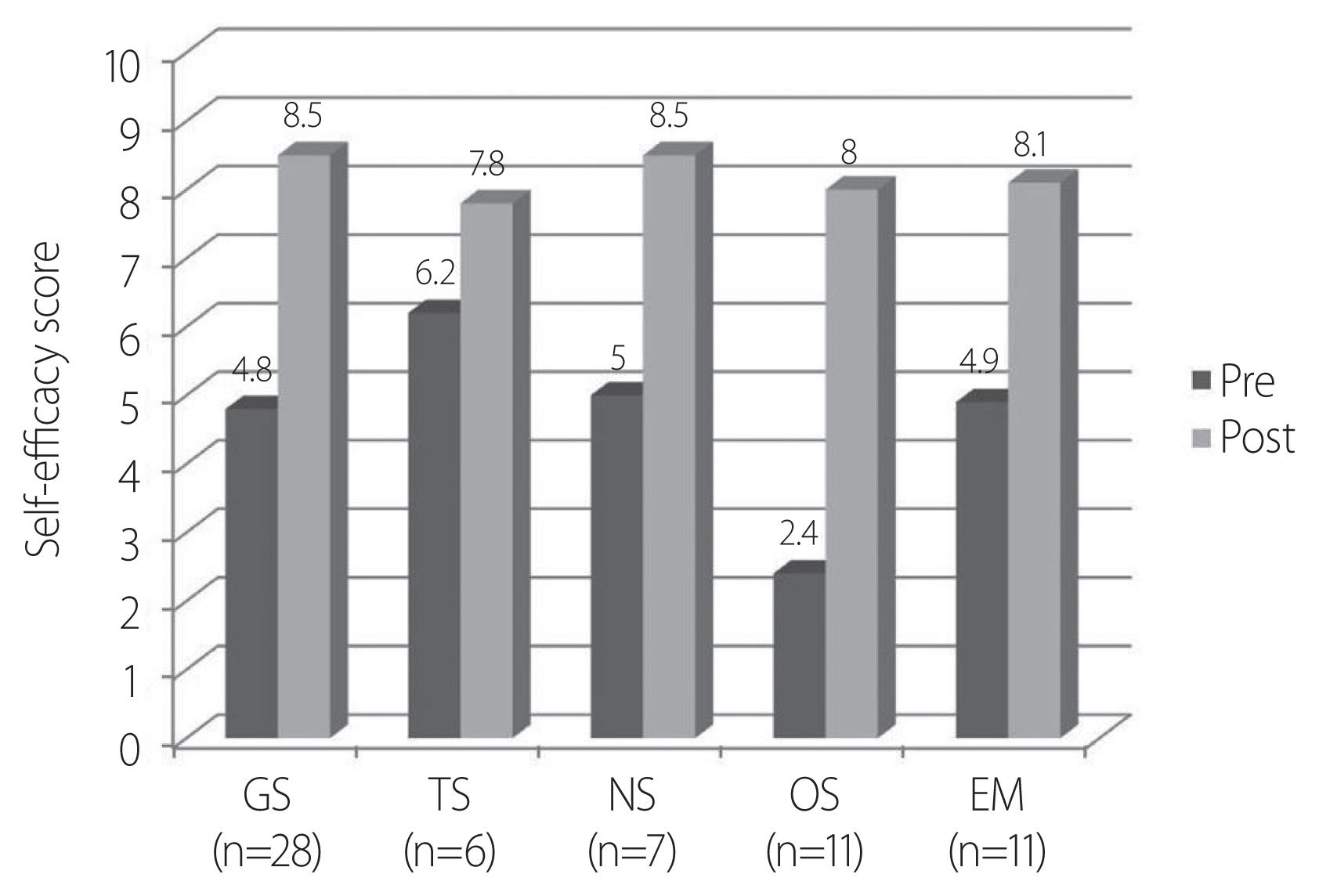

- The pre- and post-course scores divided according to working group were as follows: general surgeons, 4.8±2.14 vs. 8.5±1.21, respectively (p<0.001); thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons, 6.2±1.22 vs. 7.8±2.03, respectively (p<0.001); emergency medicine doctors, 4.9±1.95 vs. 8.1±1.11, respectively (p<0.001); orthopedic surgeons, 2.4±1.40 vs. 8.0±1.36, respectively (p<0.001); and neurosurgeons, 5.0±1.85 vs. 8.5±1.16, respectively (p<0.001) (Fig. 3). The improvement in self-efficacy score was greater in the orthopedic surgeons than in the other working Participants groups.

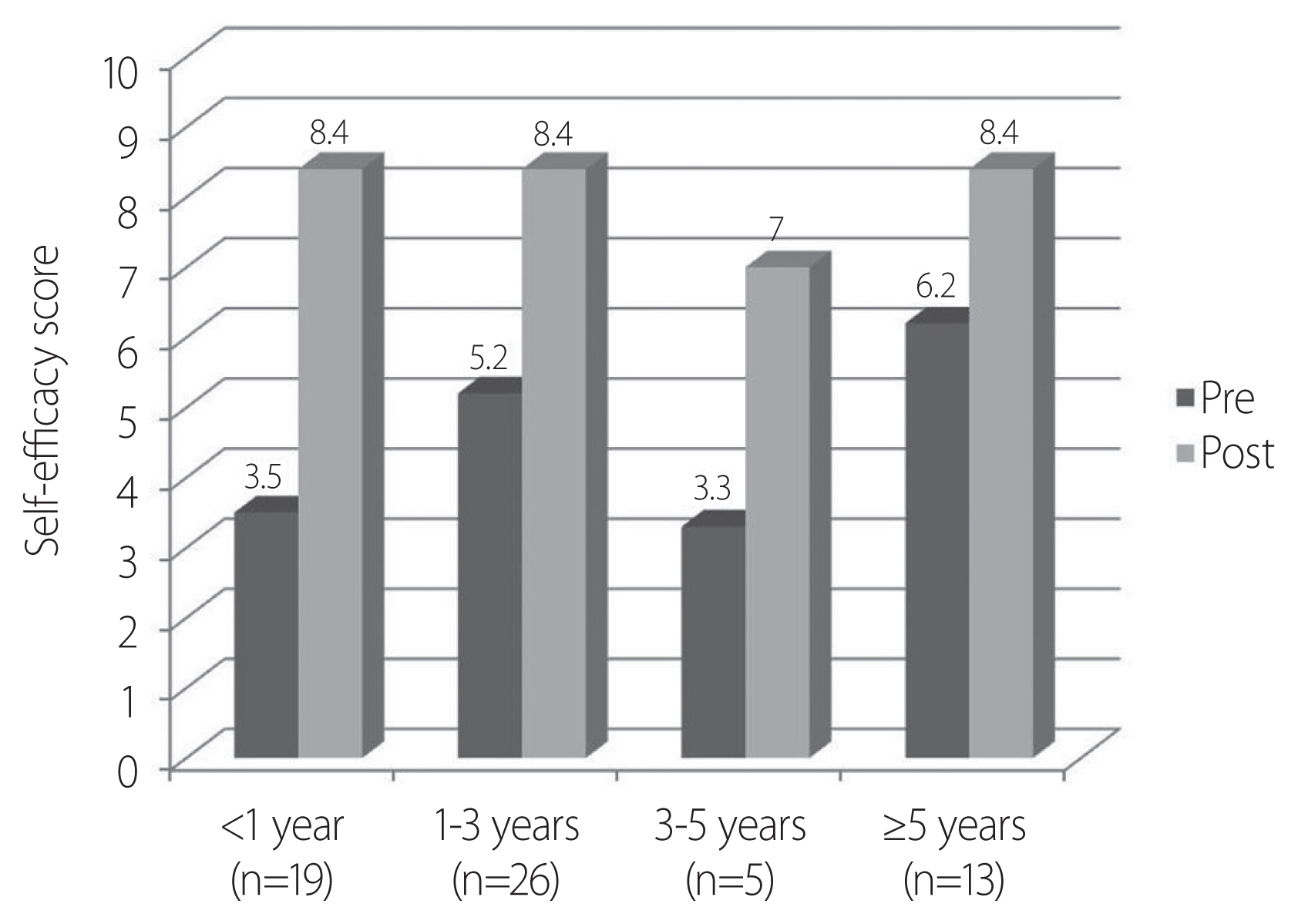

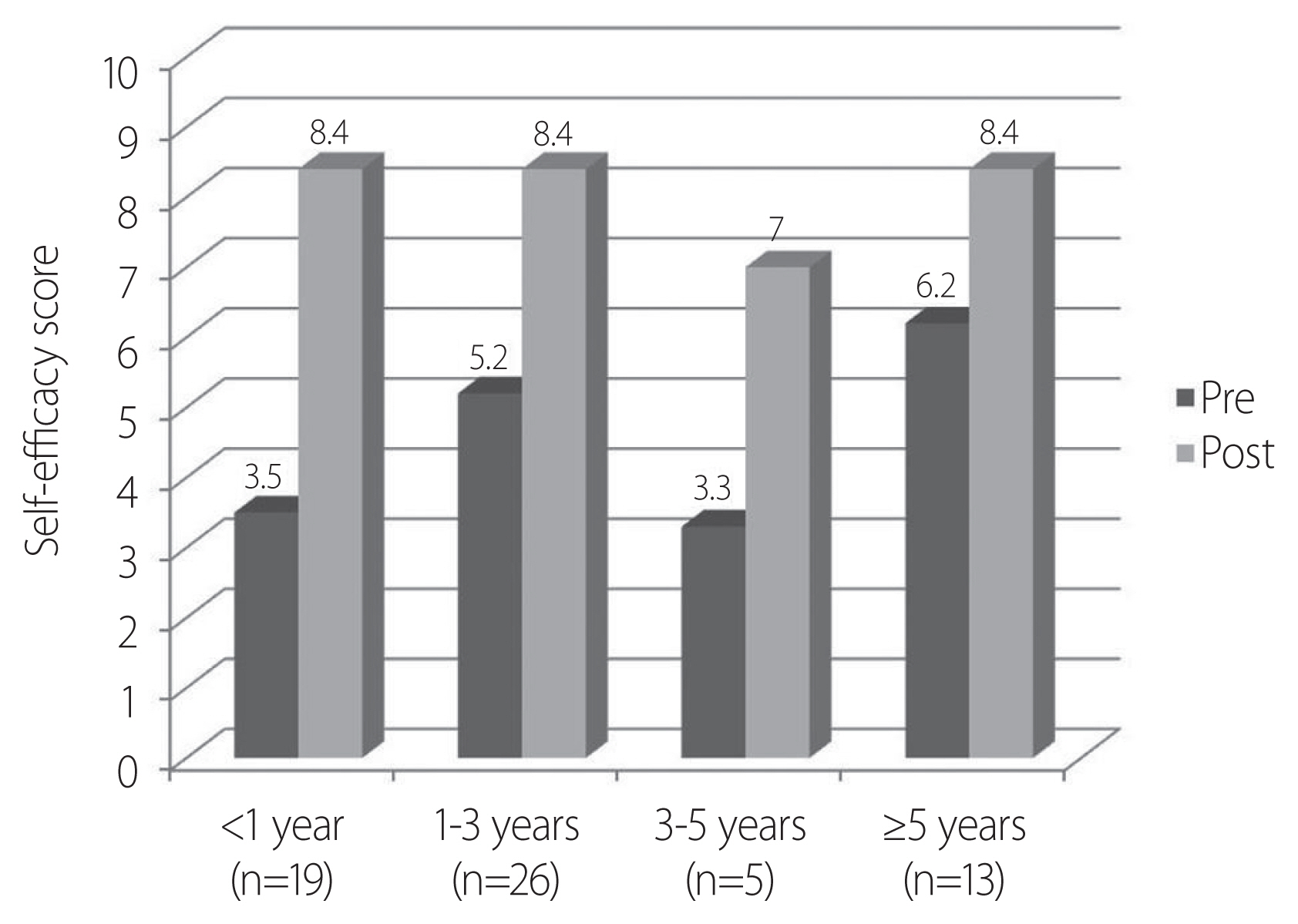

- The pre- and post-course scores according to working years were as follows: <1 year, 3.5±2.07 vs. 8.4±1.15, respectively (p<0.001); 1–3 years, 5.2±2.24 vs. 8.4±1.26, respectively (p<0.001); 3–5 years, 3.3±1.82 vs. 7.0±1.07, respectively (p<0.001); and >5 years, 5.2±1.37 vs. 8.4±1.51, respectively (p<0.001). The difference between pre- and post-course self-efficacy scores was highest in the group with <1 year of working experience (Fig. 4).

- Participants completed the course and instructor evaluations, all of which were favorable, with a mean course evaluation score of 44.7/50. Individual item scores are shown in Table 4. Participants gave scores >8 points for all evaluation items.

RESULTS

- There has been ongoing discussion regarding the low numbers of operative trauma cases and concern regarding whether this affects the competency of trauma surgeons and perceptions of this specialty [12,13]. Declining exposure to trauma surgery results in a decrease in confidence among surgeons with respect to managing injuries and the potential for increases in morbidity and mortality rates [1].

- Comparison between ATOM, DSTC, ASSET, and ESPIT

- A number of simulation courses have been developed and implemented to address the problem outlined above regarding the limited opportunities to perform trauma surgery. Table 5 shows the differences between ATOM [1–5], DSTC [9,10], ASSET [6–8], and ESPIT courses. The DSTC course was developed by a group of high experienced trauma surgeons and the International Association for the Surgery of Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care in South Africa, Europe, Australia, and the USA, and consists of 3 days of didactic lectures, a cadaver experience, an operative model, and an interactive discussion [1,9,10]. The ATOM course evolved from the DSTC course, and is a simulation course adopted by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) to teach operative management of primarily penetrating, traumatic injuries [1–5]. The ASSET course uses human cadavers for surgical exposure to anatomical structure injuries, which may confer a mortality and morbidity risk [6–8]. The ASSET course was developed by the Committee on Trauma Surgical Skills to address the need for surgical skills among residents and fellows [6–8]. DSTC and ASSET courses have not yet been held in Korea. In addition, there are no certified DSTC or ASSET instructors in Korea, and ACS or IATSIC approval is needed to modify the educational curriculum.

- In contrast, the ESPIT course is hosted by the KST, and is aimed at doctors who treat trauma, including general surgeons, thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons, neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and emergency medicine doctors. Changes in the educational curriculum are being implemented and it is constantly under development and revision. Expert panels discuss the course contents and procedures after completion of each ESPIT course, and revisions to ESPIT are made based of the judgments of these experts.

- ESPIT course

- The ESPIT course has several advantages in comparison to other educational courses. First, although the official language of the DSTC, ATOM, and ASSET courses is English, the ESPIT is in Korean, thus facilitating communication and discussion. Participants who are not competent in English may experience difficulty in lectures held in English. As most of the participants of the ESPIT course are Korean, use of the native language allows smooth communication and discussion. Second, the ESPIT course is an educational course designed according to Korean circumstances. All off-the-job training courses (e.g., ATOM and DSTC) are aimed at mastering the skills of surgical procedures in animals. The ATOM and the DSTC courses are effective methods for increasing surgical competence and confidence in operative management of penetrating injuries to the chest and abdomen, and these courses provide valid skill training [1–5,9,10]. However, cognitive strategies are required for decision-making in actual clinical environments [14–16]. Overseas courses do not necessarily correspond to the actual situation in Korea. For example, the ATOM course focuses on operative management of penetrating injuries, although blunt injuries are more common than penetrating injuries in Korea. The most recent statistics from the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for the period 2006–2016, show that blunt and penetrating injuries account for 22.7% and 11.3% of all injuries in Korea, respectively [17]. Moreover, inclusion of motor vehicle collision accidents and falls brings the proportion of blunt injuries to approximately 60% of all injuries in Korea [17]. Therefore, a training course for dealing with blunt injuries is necessary in Korea. Third, approval from ACS or IATSIC would be needed to change the educational curriculum of the DSTC, ATOM, and ASSET courses. However, the ESPIT course curriculum is flexible and has been undergoing development and revision. An expert panel discusses the course contents and procedures after completion of each ESPIT course, and revisions of course curriculum are made based on the judgments of these experts. Fourth, the ESPIT is relatively inexpensive; the ATOM and DSTC courses cost approximately $2,500 and $3,650, respectively [18,19], while the ESPIT course in Korea costs approximately $1,400. This low cost may encourage trainees to join the course and receive repeat education.

- In our study, baseline self-efficacy scores were significantly improved after the ESPIT course. Surprisingly, the differences in pre- and post-course self-efficacy scores were statistically significant for not only general/thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons, but also neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and emergency medicine doctors. This was unexpected because we initially supposed that the lectures and procedures in ESPIT would already be familiar to general/thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons (e.g., resuscitative thoracotomy, damage control laparotomy, etc.). The neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and emergency medicine doctors reported satisfaction with the contents and procedures of the course. They provided feedback indicating that this course gave them an opportunity to become cognizant of the fundamental issues and develop the basic skills of trauma surgery.

- A number of previous reports have indicated that trauma operative management courses, such as the ATOM course, are beneficial for residents and junior surgeons [1,13,16,20], with self-efficacy scores increasing along with the experience [1,16]. However, our participants were mostly specialists, and our analysis included only a few residents. Therefore, we could not determine whether the ESPIT course was beneficial to residents. The self-efficacy scores were highest in the group with <1 year of experience in our study, unlike in previous reports. Participants who had worked for <1 year seemed to have had less experience with trauma patients and were more interested in and immersed in the course.

- The above results indicated that the ESPIT course is indispensable for the acquisition of deep expertise in trauma surgery, should be designated as mandatory by the KST.

- Limitation of study

- This retrospective analysis had several limitations. First, the sample size of participants who completed the both pre- and post-course questionnaires over the 26-month study period was small (n=63). This was because many post-course questionnaires were lost early in the study. Second, neither of the domains evaluated for the ESPIT course (affective and psychomotor domains) directly measure the ability of participants in the operating room. In addition, this study was confined to participants drawn from a single educational center (MIC) and did not consider the compounding effect of heterogeneous participant characteristics. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes and further examinations, including more rigorous research design and external validation, will be necessary to draw definitive conclusions.

DISCUSSION

- In conclusion, we attempted to establish an effective and attractive training system for young trauma surgeons, emergency medicine doctors, and the other trauma-related medical practitioners, using both lectures and hands-on animal training. Data from ESPIT participants indicated that self-efficacy regarding procedures essential in trauma surgery was improved after taking the ESPIT course. Although further studies are required, the ESPIT course, the Korean teaching model for surgical procedures in trauma, may appear to be a beneficial teaching strategy for surgical education in the management of traumatic injuries.

CONCLUSION

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

-

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

The online-only data supplement is available with this article at http://doi.org/10.20408/jti.2018.051.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

| ATOM | DSTC | ASSET | ESPIT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hosted by | ACS | IATSIC | ACS | KST |

| Language | Mainly English, partly Korean | English | English | Korean |

| Country | International | International | America (USA) | Korea |

| Cost | $2,500a | $3,650a | $2,600a | $1,400a |

| Instructor | International Korean instructor (+) | International Korean Instructor (−) | International Korean instructor (−) | Korean instructor |

| To change the educational curriculum | Requires permission from ACS | Requires permission from IATSIC | Requires permission from ACS | Flexible |

ATOM: Advanced Trauma Operative Management, DSTC: Definitive Surgical Trauma Care, ASSET: Advanced Surgical Skills for Exposure in Trauma, ESPIT: Essential Surgical Procedures in Trauma, ACS: American College of Surgeons, IATSIC: International Association for the Surgery of Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care, KST: Korean Society of Traumatology.

a 2018.

- 1. Jacobs LM, Burns KJ, Kaban JM, Gross RI, Cortes V, Brautigam RT, et al. Development and evaluation of the advanced trauma operative management course. J Trauma 2003;55:471–9.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Jacobs L, Burns K, Luk S, Hull S. Advanced trauma operative management course: participant survey. World J Surg 2010;34:164–8.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 3. Jacobs LM Jr, Luk SS, Burns KJ. Advanced trauma operative management course: site and instructor selection and evaluation. J Am Coll Surg 2006;203:772–9.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Jacobs LM, Burns KJ, Luk SS, Marshall WT 3rd. Follow-up survey of participants attending the Advanced Trauma Operative Management (ATOM) Course. J Trauma 2005;58:1140–3.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Jacobs LM, Burns KJ, Luk SS, Cornwell EE 3rd, Adebonojo SA. Advanced Trauma Operative Management course introduced to surgeons in West Africa. Bull Am Coll Surg 2005;90:8–14.

- 6. Kuhls DA, Risucci DA, Bowyer MW, Luchette FA. Advanced surgical skills for exposure in trauma: a new surgical skills cadaver course for surgery residents and fellows. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:664–70.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Bowyer MW, Kuhls DA, Haskin D, Sallee RA, Henry SM, Garcia GD, et al. Advanced Surgical Skills for Exposure in Trauma (ASSET): the first 25 courses. J Surg Res 2013;183:553–8.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Ali J, Sorvari A, Haskin D, Luchette F, Bowyer M. Potential role of the Advanced Surgical Skills for Exposure in Trauma (ASSET) course in Canada. J Trauma 2011;71:1491–3.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Boffard KD. Manual of Definitive Surgical Trauma Care. 4th ed. Indiana: CRC Press; 2015.

- 10. Jacobs LM, Lorenzo C, Brautigam RT. Definitive surgical trauma care live porcine session: a technique for training in trauma surgery. Conn Med 2001;65:265–8.PubMed

- 11. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986.

- 12. Engelhardt S, Hoyt D, Coimbra R, Fortlage D, Holbrook T. The 15-year evolution of an urban trauma center: what does the future hold for the trauma surgeon? J Trauma 2001;51:633–7.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Kaban JM, Stone ME, Dayama A, Safadjou S, Reddy SH, Simon R, et al. Does resident trauma exposure affect advanced trauma operative management course experience? Am Surg 2016;82:212–5.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Sullivan S, Campbell K, Ross JC, Thompson R, Underwood A, LeGare A, et al. Identifying nontechnical skill deficits in trainees through interdisciplinary trauma simulation. J Surg Educ 2018;75:978–83.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Sparks JL, Crouch DL, Sobba K, Evans D, Zhang J, Johnson JE, et al. Association of a surgical task during training with team skill acquisition among surgical residents: the missing piece in multidisciplinary team training. JAMA Surg 2017;152:818–25.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Moorman ML, Capizzani TR, Feliciano MA, French JC. A competency-based simulation curriculum for surgical resident trauma resuscitation skills. Int J Crit Ill Inj Sci 2017;7:241–7.Article

- 17. Ann SH, Seo SH, Kim BA, Lee KE, Kim YT. Emergency department-based injury in-depth surveillance data, 2006–2015. Public Health Weekly Report 2016;9:651–5.

- 18. Definitive Surgical Trauma Care (DSTC). Definitive Surgical Trauma Care Courses [Internet]. DSTC; 2018 [cited 2018 Jun 5]. Available from: https://dstc.com.au/#registration.

- 19. University of California San Diego School of Medicine. Advanced Trauma Operative Management Course [Internet]. San Diego: University of California; 2018 [cited 2018 Jun 5]. Available from: https://medschool.ucsd.edu/som/surgery/divisions/trauma-burn/training/courses/Pages/atom.aspx.

- 20. Ali J, Ahmed N, Jacobs LM, Luk SS. The advanced trauma operative management course in a Canadian residency program. Can J Surg 2008;51:185–9.PubMedPMC

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

KST

KST

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite